Last week, two wireless internet service providers called me about the same problem. Their external network hardware was failing. Not gradually. Completely.

One was on Cape Cod. The other in upstate New York. Different locations, same mistake: they installed residential-grade access points outside and assumed they’d be fine.

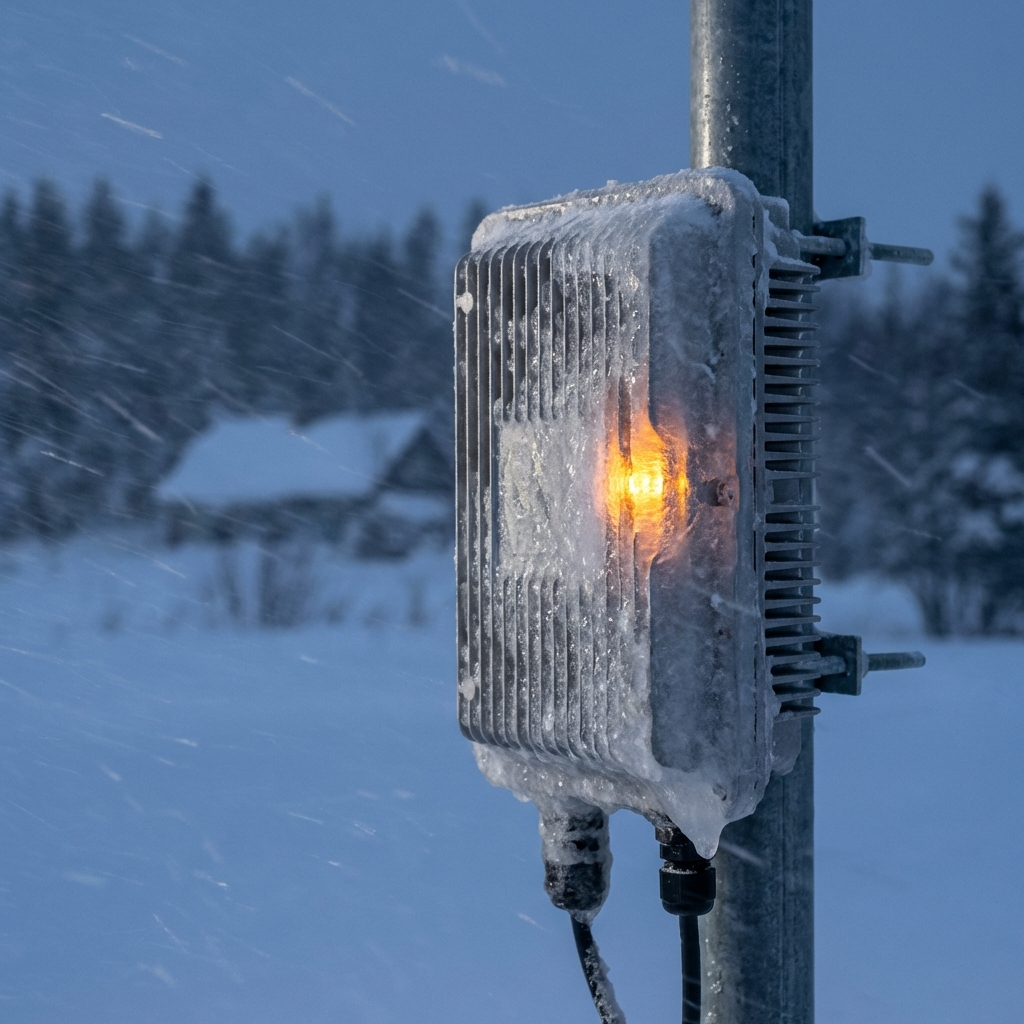

The Northeast is getting hit with temperatures dropping to -20°F. Wind-driven snow. Ice accumulation. This is when you find out if your external network hardware can actually survive the environment you put it in.

Most businesses discover the answer when their network goes down.

The Real Cost of Choosing Residential-Grade Hardware

Residential-grade access points cost between $100 and $200. Commercial-grade weather-resistant hardware runs $300 to $500 or more.

That $200 difference looks like savings until your system fails.

I’ve watched businesses try to justify the cheaper option by buying extras. “If one fails, I’ll just replace it.” They don’t realize that when water shorts out the external unit, it travels down the wire. That water can reach your network switch in the basement or service closet and burn it out too.

The average cost of network downtime is $5,600 per minute. That’s over $336,000 per hour. Even for small businesses, downtime costs between $137 and $427 per minute.

Your $200 savings disappears in the first three minutes of an outage.

What Actually Happens When Hardware Fails

The two biggest threats are extreme cold and water penetration.

People underestimate how wind pushes water upward into equipment that appears sheltered. They don’t account for capillary action—water traveling through the twisted pairs inside network cables, destroying electrical characteristics as it goes.

When external hardware fails in a network bridge setup, you get complete network collapse at any non-centralized point. Communication stops. Monitoring stops. If you’re running environmental monitoring systems, you lose visibility into critical infrastructure.

In some cases, you can’t reach emergency services because the entire communication network is down.

This isn’t theoretical. Hardware failure accounts for 55% of all downtime events in small and medium-sized businesses. Consumer-grade equipment has significantly higher failure rates because it’s built to lower specifications.

Why Commercial-Grade Hardware Actually Matters

Commercial and enterprise-grade systems are designed around the environments they’ll operate in.

Residential systems aren’t. They’re built for climate-controlled indoor spaces with minimal stress. When you scale your business or encounter extreme weather—which is happening more frequently—that hardware can’t keep up.

The reliability gap is substantial. Enterprise-grade hardware is designed to last ten to thirty years without failure. Consumer equipment? Some manufacturers see failure rates of 3-4%, with most failures occurring within the first 30 days.

Here’s what matters: longevity, productivity, and functionality.

When you start with proper commercial-grade hardware, you don’t have to replace your entire network when you grow. The system scales with you. When you start cheap, you’re replacing everything within three years—sometimes twice in that period.

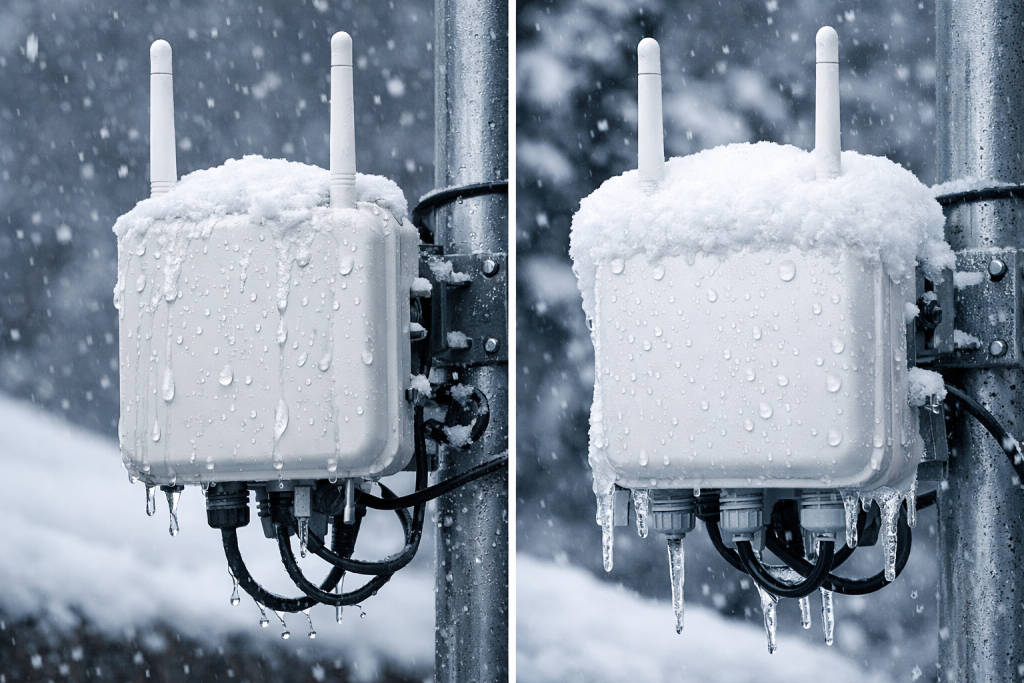

Environmental Ratings You Need to Understand

IP ratings tell you what conditions hardware can withstand.

IP65 provides complete dust protection and protects against low-pressure water jets from any direction. It handles rain, splashes, and hose cleaning.

IP67 goes further. It protects against temporary submersion up to 1 meter deep for 30 minutes.

But here’s what the ratings don’t tell you: IP65 should not be interpreted as full protection against prolonged heavy rain, flooding, or high-pressure washdown. For permanent external installations, you want IP66 or IP67 minimum.

If you’re in eastern Massachusetts, particularly Cape Cod, you need hardware certified by the Cape Cod Technology Council. Their standards are high enough that I recommend using their approved hardware list regardless of your location. If you underestimate environmental threats, you’re still covered.

Check the operating temperature range. Your hardware needs to function at the lowest temperature your location will ever encounter. Not the average winter temperature. The absolute minimum.

Installation Mistakes That Void Weather Resistance

Proper installation and sealing determine whether rated equipment actually performs as rated.

I’ve seen IP67-rated enclosures fail because gaskets weren’t fitted correctly. I’ve watched installers mount hardware on a sunny day and assume it would stay that way.

Here’s what you need to verify:

Network jacks must face downward. Even in worst-case scenarios, water flows over them instead of into them.

Install rubber gaskets or anti-electrolytic gel. Standard PVC coating on data cables is hygroscopic—it attracts and holds water. One test showed Cat6 Riser indoor cable failing both ANSI/TIA Cat6 and 5GBASE-T bandwidth tests within two hours of water exposure.

Create a three-foot service loop. This lets you service the device, but more importantly, it prevents water from traveling straight down the cable into your infrastructure.

Ground any metal components properly. Lightning strikes, surges, and electromagnetic interference need a path that doesn’t run through your equipment.

Read the manufacturer’s installation instructions. “Outdoor rated” can mean protected enclosure, not direct weather exposure. The difference matters.

Water and electricity both follow the path of least resistance. If that path leads to a misaligned access point or improperly sealed connection, they’ll find it. We’re APC Power Protection specialists, so we’ve been trained on how water, electricity, fire, and lightning interact. The principles are the same.

Skip these steps and you void the weather resistance you paid for.

The Hurricane Sandy Lesson

In 2012, Hurricane Sandy filled basements and telecom closets across New York with water. That water traveled through copper lines via capillary action.

Verizon gave the FCC an ultimatum: restoring copper would take 20 to 30 years. Replacing it with fiber would take three to six months. The FCC changed the rules. Verizon restored telecom service in six months.

The same principle applies to your external network hardware. When water shorts out the external device, it travels back to your network switch. You’re not just replacing the access point. You’re replacing:

- The burned-out switch

- The damaged cabling

- Power infrastructure

- Grounding systems

Labor costs for embedded systems that need to be gutted and reinstalled are exponentially higher than initial installation costs. In Massachusetts, low-voltage wiring requires permits during rehab work. Your insurance company will want documentation, certifications, and proof that licensed electricians did the work.

Residential or self-installed systems don’t qualify when an inspector shows up.

I’ve seen installations I did properly run for ten-plus years. I’ve watched businesses next door—same environment—replace their self-installed systems twice in three years. They’ve now spent more on replacements and emergency service calls than the commercial-grade hardware would have cost initially.

How to Audit Your Current Installation

Walk outside and look at your external network hardware right now.

Check the technical specifications. What’s the minimum operating temperature? What’s the IP rating? Does it match the actual conditions at your location?

Inspect the mounting. Are network jacks facing down? Are cables creating a service loop, or do they run straight into the device?

Look for gaskets and seals. Are they present? Are they properly fitted? Have they degraded?

Verify grounding. If the device has metal components or is attached to metal, is it properly grounded?

Review the manufacturer’s installation guide. Does your current setup match their specifications?

Check for “outdoor rated” versus “weather resistant.” One means protected enclosure. The other means direct exposure. Which one do you actually have?

If you’re near large bodies of water, verify that your Wi-Fi systems account for DFS (Dynamic Frequency Selection). The Navy remaps areas periodically. When radar is detected, Wi-Fi and bridges on certain frequencies shut down automatically. Experience with spectrum management prevents this from becoming an unexpected outage.

Document what you find. You’ll need this information for the next step.

What Documentation You Need

Your insurance company may not cover hardware losses from environmental events like hurricanes, tornadoes, or ice storms if you haven’t declared the equipment properly.

Collect this documentation now:

Technical specifications for all installed hardware. Operating temperature ranges, IP ratings, certifications.

Installation records from your vendor or electrician. Permits, inspection reports, certification documentation.

Manufacturer installation guides. Proof that you followed specified procedures.

Floor plans showing equipment locations. Helpful for insurance claims and replacement planning.

Records of previous weather events or insurance losses. Establishes patterns and justifies upgrades.

Review your insurance policy 90 days before renewal. Have a third party review it with you. You may think everything is covered when it’s not.

Work with your insurance provider to verify coverage. When they ask for details, you need documentation ready. The goal isn’t ultra-detailed reports. The goal is having answers when questions come up.

Make sure the person who installed your system has experience and certifications with wireless systems and external installations. Someone with a truck and toolbox isn’t qualified. I’ve seen licensed electricians misapply indoor methodologies to outdoor environments because they don’t understand environmental requirements.

What This Means for Your Business

The choice isn’t really about hardware specifications or IP ratings.

It’s about whether you’re making decisions based on upfront cost or total cost of ownership.

Residential-grade hardware costs less initially. Commercial-grade hardware costs less over time. The difference shows up in downtime costs, replacement cycles, labor expenses, permit requirements, and insurance coverage.

Research shows that 59% of surveyed professionals think climate change will cause more IT service outages. 86% believe it will drive up infrastructure and operations costs over the next ten years.

Extreme weather events are becoming more frequent. The hardware decisions you make now determine whether you’re prepared or vulnerable.

Start with quality hardware installed properly. Document everything. Verify coverage with your insurance provider. Audit your current installations before the next weather event.

The businesses that do this work now won’t be the ones calling for emergency service when temperatures drop to -20°F.